By Steven A. Camarota and Karen Zeigler on December 2, 2018

Immigration Research Archives

Terrorist Infiltration Threat at the Southwest Border – CIS.org

Center for Immigration Studies

Terrorist Infiltration Threat at the Southwest Border

The national security gap in America’s immigration enforcement debate

By Todd Bensman on August 13, 2018

Todd Bensman is a senior national security fellow at the Center for Immigration Studies.

Introduction

“On June 24, 2016 — during the waning days of President Barack Obama’s administration — Department of Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson sent a three-page memorandum To 10 top law enforcement chiefs responsible for border security.1 The subject line referenced a terrorism threat at the nation’s land borders that had been scarcely acknowledged by the Obama administration during its previous seven years. So far, it also has evaded much mention in national debate over Trump administration immigration policy.

The subject line read: “Cross-Border Movement of Special Interest Aliens”.

What followed were orders, unusual in the sense that they demanded the “immediate attention” of the nation’s most senior immigration and border security leaders to counter such an obscure terrorism threat.

Secretary Johnson ordered that they form a “multi-DHS Component SIA Joint Action Group” and produce a “consolidated action plan” to take on this newly important threat. He was referring to the smuggling of migrants from Muslim-majority countries, often across the southern land border — a category of smuggled persons likely already known to memo recipients as special interest aliens, or SIAs. Secretary Johnson provided few clues for the apparent urgency, except to state: “As we all appreciate, SIAs may consist of those who are potential national security threats to our homeland. Thus, the need for continued vigilance in this particular area.” Elsewhere, the secretary cited “the increased global movement of SIAs.”

The unpublicized copy of the memo, obtained by CIS, outlined plan objectives. Intelligence collection and analysis, Secretary Johnson wrote, would drive efforts to “counter the threats posed by the smuggling of SIAs.” Coordinated investigations would “bring down organizations involved in the smuggling of SIAs into and within the United States.” Border and port of entry operations capacities would “help us identify and interdict SIAs of national security concern who attempt to enter the United States” and “evaluate our border and port of entry security posture to ensure our resources are appropriately aligned to address trends in the migration of SIAs.”

Secretary Johnson saw a need to educate the general public about what was about to happen. Public affairs staffs would craft messaging that the new program would “protect the United States and our partners against this potential threat.”

However, no known Public Affairs Office education about SIA immigration materialized as Secretary Johnson and most of his agency heads were swept out of office some months later by the election of Republican President Donald Trump. Whatever reputed threat about which the Obama administration wanted to inform the public near its end remains narrowly known. So, too, are whatever operations developed from the secretary’s 2016 directive.

Perhaps notably, the cross-border migration of people from Muslim-majority nations, as a trending terror threat, has gone missing during contentious national debates over President Trump’s border security policies and wall. Most discourse has been confined to Spanish-speaking border entrants rather than on those who speak Arabic, Pashtun, and Urdu.

So what is an SIA and why, in 2016, did this “potential national security threat” require the urgent coordinated attention of agencies, with not much word about it since? This Backgrounder provides a factual basis necessary for anyone inclined to add the prospect of terrorism border infiltration, via SIA smuggling, to the nation’s ongoing discourse about securing borders.

It provides a definition of SIAs and a history of how homeland security authorities have addressed the issue since 9/11. Since SIA immigration traffic is the only kind with a distinct and recognized terrorism threat nexus, its apparent sidelining from the national debate presents a particular puzzlement.

No illegal border crosser has committed a terrorist attack on U.S. soil, to date. A Somali asylum-seeker who crossed the Mexican border to California in 2011 did allegedly commit an ISIS-inspired attack in Canada, wounding five people in 2017, and numerous SIAs with terrorism connections reportedly have been apprehended at the southern border, to include individuals said to be linked to designated terrorist organizations in Somalia, Sri Lanka, Lebanon, and Bangladesh.2 But while most SIAs likely have no terrorism connectivity, the purpose of this Backgrounder is not to assess the perceived degree of any actual terrorist infiltration threat. The purpose, rather, is to establish a less disputable basis for discourse and action by either Republicans or Democrats through a homeland security lens: That SIA smuggling networks provide the capability for terrorist travelers to reach the border, and also that legislation-driven strategy requires U.S. agencies to tend to the issue regardless.3

The rest of the report can be read here.

Video: How SIAs Reach the U.S. Through South and Central America

Center for Immigration Studies

December 17, 2018

Video: How SIAs Reach the U.S. Through South and Central America

They can reach the main lanes of Central America leading to the United States the easy way, or the hard way. This video documents the hard way.

CIS: Nearly One in Seven U.S. Residents Are Now Immigrants

Center for Immigration Studies

Nearly One in Seven U.S. Residents Are Now Immigrants

Highest foreign-born share in 107 years

September 14, 2018

Washington, D.C. (September 14, 2018) – A report by the Center for Immigration Studies analyzes new data from the 2017 American Community Survey (ACS), released by the Census Bureau Thursday, showing the nation’s immigrant population (legal and illegal) has reached 44.5 million – the highest number in U.S. history. Growth was led by immigrants from Latin American countries other than Mexico, as well as Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. The number from Mexico, Europe and Canada either remained flat or declined since 2010. The Census Bureau refers to immigrants as the foreign-born population.

“America continues to experience the largest wave of mass immigration in our history. The decline in Mexican immigrants has been entirely offset by immigration from the rest of the world. By 2027, the immigrant share will hit its highest level in U.S. history, and continue to rise,” said Steven Camarota, the Center’s director of research and co-author of the report.

Read the Report: https://cis.org/Report/Record-445-Million-Immigrants-2017

Key findings:

- As a share of the U.S. population, immigrants (legal and illegal) comprised 13.7 percent or nearly one out of seven U.S. residents in 2017, the highest percentage since 1910.

- The number of immigrants hit a record 44.5 million in 2017, an increase of nearly 800,000 since 2016, 4.6 million since 2010, and 13.4 million since 2000.

- There were also 17.1 million U.S.-born minor children of immigrants in 2017, for a total of 61.6 million immigrants and their young children in the country — accounting for one in five U.S. residents.

- Between 2010 and 2017, 9.5 million new immigrants settled in the United States. New arrivals are offset by roughly 300,000 immigrants who return home each year and natural mortality of about 300,000 annually. As a result, the immigrant population grew 4.6 million from 2010 to 2017.

- The 9.5 million new arrivals since 2010 roughly equals the entire immigrant population in 1970.

- Of immigrants who have arrived since 2010, 13% or 1.3 million came from Mexico — by far the top sending country. However, because of return migration and natural mortality among the existing population, the overall Mexican-born population actually declined by 441,190.

- The regions with largest numerical increases since 2010 were East Asia and South Asia (each up 1.1 million), the Caribbean (up 676,023), Sub-Saharan Africa (up 606,835), South America (up 483,356), Central America (up 474,504), and the Middle East (472,554).

- The decline in Mexican immigrants masks, to some extent, the enormous growth of Latin American immigrants. If seen as one region, the number from Latin America (excluding Mexico) grew 426,536 in just the last year and 1.6 million since 2010.

- The sending countries with the largest increases in the number immigrants since 2010 were India (up 830,215), China (up 677,312), the Dominican Republic (up 283,381), Philippines (up 230,492), Cuba (up 207,124), El Salvador (up 187,783), Venezuela (up 167,105), Colombia (up 146,477), Honduras (up 132,781), Guatemala (up 128,018), Nigeria (up 125,670), Brazil (up 111,471), Vietnam (up 102,026), Bangladesh (up 95,005), Haiti (up 92,603), and Pakistan (up 92,395).

- The sending countries with the largest percentage increases since 2010 were Nepal (up 120%), Burma (up 95%), Venezuela (up 91%), Afghanistan (up 84%), Saudi Arabia (up 83%), Syria (up 75%), Bangladesh (up 62%), Nigeria (up 57%), Kenya (up 56%), India (up 47%), Iraq (up 45%), Ethiopia (up 44%), Egypt (up 34%), Brazil (up 33%), Dominican Republic and Ghana (up 32%), China (up 31%), Pakistan (up 31%), and Somalia (up 29%).

- The states with the largest increases in the number of immigrants since 2010 were Florida (up 721,298), Texas (up 712,109), California (up 502,985), New York (up 242,769), New Jersey (up 210,481), Washington (up 173,891), Massachusetts (up 172,908), Pennsylvania (up 154,701), Virginia (up 151,251), Maryland (up 124,241), Georgia (up 123,009), Michigan (up 116,059), North Carolina (up 110,279), and Minnesota (up 107,760).

- The states with the largest percentage increase since 2010 were North Dakota (up 87%), Delaware (up 37%), West Virginia (up 33%), South Dakota (up 32%), Wyoming (up 30%), Minnesota (up 28%), Nebraska (up 28%), Pennsylvania (up 21%), Utah (up 21%), Tennessee, Kentucky, Michigan, Florida, Washington, and Iowa (each up 20%). The District of Columbia’s immigrant population was up 25%. Read the rest here.

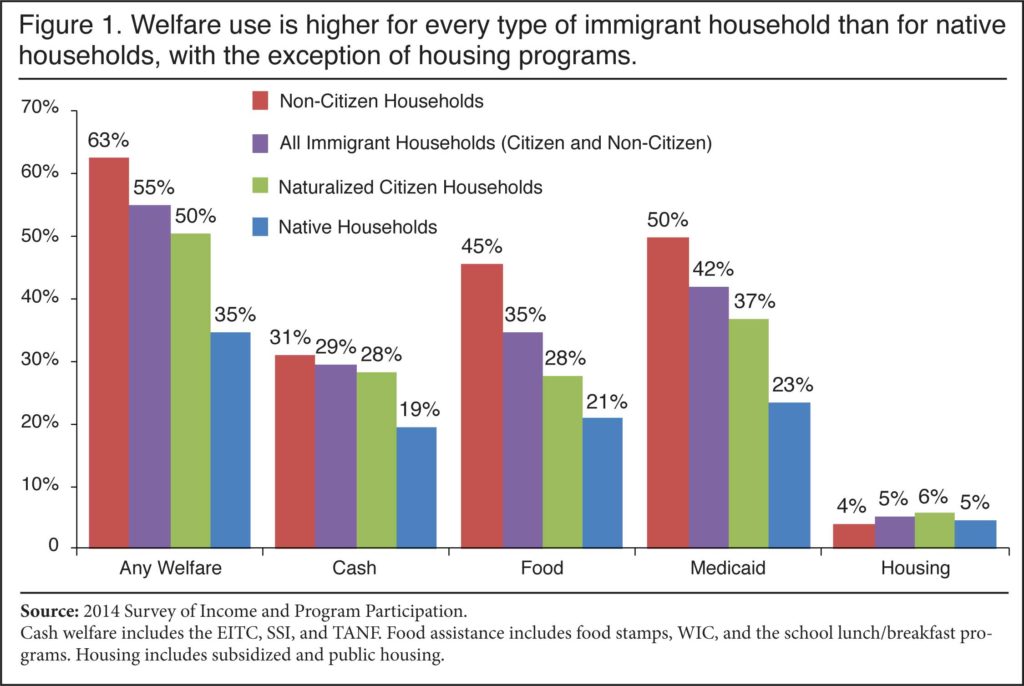

63% of Non-Citizen Households Access Welfare Programs – Compared to 35% of native households

Center for Immigration Studies

CIS.org

63% of Non-Citizen Households Access Welfare Programs

Compared to 35% of native households

Download a PDF of this Backgrounder.

Steven A. Camarota is the director of research and Karen Zeigler is a demographer at the Center.

New “public charge” rules issued by the Trump administration expand the list of programs that are considered welfare, receipt of which may prevent a prospective immigrant from receiving lawful permanent residence (a green card). Analysis by the Center for Immigration Studies of the Census Bureau’s Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) shows welfare use by households headed by non-citizens is very high. The desire to reduce these rates among future immigrants is the primary justification for the rule change. Immigrant advocacy groups are right to worry that the high welfare use of non-citizens may impact the ability of some to receive green cards, though the actual impacts of the rules are unclear because they do not include all the benefits non-citizens receive on behalf of their children and many welfare programs are not included in the new rules. As welfare participation varies dramatically by education level, significantly reducing future welfare use rates would require public charge rules that take into consideration education levels and resulting income and likely welfare use.

Of non-citizens in Census Bureau data, roughly half are in the country illegally. Non-citizens also include long-term temporary visitors (e.g. guestworkers and foreign students) and permanent residents who have not naturalized (green card holders). Despite the fact that there are barriers designed to prevent welfare use for all of these non-citizen populations, the data shows that, overall, non-citizen households access the welfare system at high rates, often receiving benefits on behalf of U.S.-born children.

Among the findings:

- In 2014, 63 percent of households headed by a non-citizen reported that they used at least one welfare program, compared to 35 percent of native-headed households.

- Welfare use drops to 58 percent for non-citizen households and 30 percent for native households if cash payments from the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) are not counted as welfare. EITC recipients pay no federal income tax. Like other welfare, the EITC is a means-tested, anti-poverty program, but unlike other programs one has to work to receive it.

- Compared to native households, non-citizen households have much higher use of food programs (45 percent vs. 21 percent for natives) and Medicaid (50 percent vs. 23 percent for natives).

- Including the EITC, 31 percent of non-citizen-headed households receive cash welfare, compared to 19 percent of native households. If the EITC is not included, then cash receipt by non-citizen households is slightly lower than natives (6 percent vs. 8 percent).

- While most new legal immigrants (green card holders) are barred from most welfare programs, as are illegal immigrants and temporary visitors, these provisions have only a modest impact on non-citizen household use rates because: 1) most legal immigrants have been in the country long enough to qualify; 2) the bar does not apply to all programs, nor does it always apply to non-citizen children; 3) some states provide welfare to new immigrants on their own; and, most importantly, 4) non-citizens (including illegal immigrants) can receive benefits on behalf of their U.S.-born children who are awarded U.S. citizenship and full welfare eligibility at birth. Read the entire report here.

Immigration Research Archives

Research test for archives

[ whohit]Research Archives[ /whohit]

What is “Chain Migration?”

NumbersUSA.com

NumbersUSA.com

Chain Migration refers to the endless chains of foreign nationals who are allowed to immigrate to the United States because citizens and lawful permanent residents are allowed to sponsor their non-nuclear family members.

HOW CHAIN MIGRATION WORKS

Chain Migration starts with a foreign citizen chosen by our government to be admitted on the basis of what he/she is supposed to offer in our national interest. The Original Immigrant is allowed to bring in his/her nuclear family consisting of a spouse and minor children. After that, the chain begins. Once the Original Immigrant and his/her spouse becomes a U.S. citizen, they can petition for their parents, adult sons/daughters and their spouses and children, and their adult siblings.

The Family-Chain categories are divided into four separate preferences:

- 1st Preference: Unmarried sons/daughters of U.S. citizens and their children (capped at 23,400/year)

- 2nd Preference: Spouses, children, and unmarried sons/daughters of green card holders (capped at 114,000/year)

- 3rd Preference: Married sons/daughters of U.S. citizens and their spouses and children (capped at 23,400/year)

- 4th Preference: Brothers/sisters of U.S. citizens (at least 21 years of age) and their spouses and children (capped at (65,000/year.

- Read more from NumbersUSA here

Birthright Citizenship: An Overview

Center for Immigration Studies

Art Arthur

November 5, 2018

Birthright Citizenship: An Overview

Andrew R. Arthur is a resident fellow in law and policy at the Center for Immigration Studies.

Summary

- The issue of birthright citizenship, as it pertains to children born in the United States to aliens unlawfully present, remains an open question. Although this fact would appear to be resolved in the public imagination, it has not actually been ruled upon dispositively by the Supreme Court. President Trump’s assertion that he would end birthright citizenship by an as-yet-unpublished executive order has brought this issue into focus. Should he issue such an executive order, it would provide the Supreme Court the opportunity to resolve the issue once and for all.

- Citizenship is currently offered to all children who are born in 39 countries (with the exception of children of diplomats), most of which are in the Western Hemisphere. No country in Western Europe offers birthright citizenship without exceptions to all children born within their borders.1

- Many countries, including France, New Zealand, and Australia, have abandoned birthright citizenship in the past few decades.2 Ireland was the last country in the European Union to follow the practice, abolishing birthright citizenship in 2005.3

- The costs of births for the children of illegal aliens is staggering. The Center for Immigration Studies (CIS) estimates that in 2014, $2.35 billion in taxpayer funding went to pay for more than 273,000 births to illegal immigrants.4

Introduction

President Trump’s recent pronouncement that he plans to sign an executive order to end birthright citizenship has brought that issue, which has been debated for the last 150 years, to the fore. According to Quartz, 39 countries currently offer citizenship to persons born therein, with the exception of children of diplomats, most of which are in the Western Hemisphere.5

Most of our major allies do not follow the practice. The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) World Factbook, for example, states that Germany does not offer citizenship by birth, and offers citizenship by descent only if at least one parent is a German citizen or a resident alien who has lived in Germany for at least eight years.6 Similarly, according to the CIA, the United Kingdom does not offer birthright citizenship, and offers citizenship by descent only if at least one parent is a citizen of the United Kingdom.7

As The Atlantic has noted, many countries that used to have birthright citizenship have done away with the practice.8 It explains:

France did away with birthright citizenship in 1993, following the passage of the Méhaignerie Law. The law limited citizenship to those born to a French parent, or to a parent also born in France. As a result, those born in France to foreign-born parents must wait until they turn 18 to automatically acquire French citizenship (a process that can begin when they turn 13, if they apply).

Ireland was the last of the European Union countries to abolish birthright citizenship, in 2005. Through a referendum backed by nearly 80 percent of Irish voters, citizenship was limited to those born to at least one Irish parent. The decision was a response to a controversy surrounding birth tourism and the high-profile case of Man Levette Chen, a Chinese national who traveled to Northern Ireland so that her daughter would be born an Irish citizen. Chen sought residency rights in Britain, citing her child’s Irish and EU citizenship. Though the United Kingdom Home Office rejected Chen’s application, the decision was overturned by the European Court of Justice in 2004.

Other countries, including New Zealand and Australia, have also abolished their birthright-citizenship laws in recent years. The latest is the Dominican Republic, whose supreme court ruled to remove the country’s birthright laws in 2013. The decision retroactively stripped tens of thousands of people born to undocumented foreign parents of their citizenship and rendered them “ghost citizens,” according to Amnesty International.

Benefits of U.S. Citizenship

United States citizenship is one of, if not the, most exulted and prized statuses in the world. Citizenship in this country offers the most significant economic opportunities. It guarantees the fullest protection of our laws and of the security afforded by our military servicemen and -women around the world. And, most importantly, it provides the chance to participate in the world’s oldest existing democracy.9

As an immigration judge, I was honored to have had the authority and opportunity to administer the oath of allegiance and renunciation to new citizens.10 In addition, I was often called upon to adjudicate cases in which an individual charged as an alien with removability claimed instead to be a citizen of the United States, either by birth or derivation.

Significantly, while there are many benefits that the Constitution and laws of the United States grant to both citizens and aliens, certain benefits are available only to U.S. citizens. These include the right to vote, priority when it comes to bringing family members to the United States, the ability to convey citizenship to a child born abroad, travel with a U.S. passport, and eligibility for most federal jobs and elected offices.11

More prosaically, U.S. citizens have access to many forms of government benefits that are not, as a rule, available to aliens, even to many aliens lawfully present in the United States.12 Specifically, citizens are not subject to restrictions for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly food stamps), the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) cash assistance, and Medicaid that apply to certain categories of aliens in the United States.13 In addition, citizens are not barred from receiving federal student aid, as certain aliens are.14

Most significantly, however, U.S. citizens are not amenable to removal from the United States, unless they have been denaturalized.15

Becoming a Citizen

Understanding the benefits of U.S. citizenship, the question is then how one becomes a citizen. As the Congressional Research Service (CRS) has explained: “United States citizenship is conferred at birth both under the principle of jus soli (nationality of place of birth) and the principle of jus sanguinis (nationality of parents).”16 With respect to these individuals, section 301 of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) states that:

The following shall be nationals and citizens of the United States at birth:

(a) a person born in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof;

(b) a person born in the United States to a member of an Indian, Eskimo, Aleutian, or other aboriginal tribe: Provided, That the granting of citizenship under this subsection shall not in any manner impair or otherwise affect the right of such person to tribal or other property;

(c) a person born outside of the United States and its outlying possessions of parents both of whom are citizens of the United States and one of whom has had a residence in the United States or one of its outlying possessions, prior to the birth of such person;

(d) a person born outside of the United States and its outlying possessions of parents one of whom is a citizen of the United States who has been physically present in the United States or one of its outlying possessions for a continuous period of one year prior to the birth of such person, and the other of whom is a national, but not a citizen of the United States;

(e) a person born in an outlying possession of the United States of parents one of whom is a citizen of the United States who has been physically present in the United States or one of its outlying possessions for a continuous period of one year at any time prior to the birth of such person;

(f) a person of unknown parentage found in the United States while under the age of five years, until shown, prior to his attaining the age of twenty-one years, not to have been born in the United States;

(g) a person born outside the geographical limits of the United States and its outlying possessions of parents one of whom is an alien, and the other a citizen of the United States who, prior to the birth of such person, was physically present in the United States or its outlying possessions for a period or periods totaling not less than five years, at least two of which were after attaining the age of fourteen years: Provided, That any periods of honorable service in the Armed Forces of the United States, or periods of employment with the United States Government or with an international organization as that term is defined in section 1 of the International Organizations Immunities Act (59 Stat. 669; 22 U.S.C. 288) by such citizen parent, or any periods during which such citizen parent is physically present abroad as the dependent unmarried son or daughter and a member of the household of a person (A) honorably serving with the Armed Forces of the United States, or (B) employed by the United States Government or an international organization as defined in section 1 of the International Organizations Immunities Act, may be included in order to satisfy the physical-presence requirement of this paragraph. This proviso shall be applicable to persons born on or after December 24, 1952, to the same extent as if it had become effective in its present form on that date; and

(h) a person born before noon (Eastern Standard Time) May 24, 1934, outside the limits and jurisdiction of the United States of an alien father and a mother who is a citizen of the United States who, prior to the birth of such person, had resided in the United States.17

In addition, as noted, aliens may become naturalized citizens18 and “[o]n occasion, Congress has collectively naturalized the population of a territory upon its acquisition by the United States, though in these instances individuals have at times been given the option of retaining their former nationality.”19

CIS fact sheet: E-Verify

Center for Immigration Studies

October 18, 2018

E-Verify Fact Sheet

“In recent years, many states have enacted enforcement-focused immigration laws in an effort to discourage illegal immigration into their jurisdictions. E-Verify, the federally run employment authorization program, has become a central part of this state-level effort as many states now require use of the program for some or all employers. E-Verify is an Internet-based system that allows businesses to determine the eligibility of their employees to work in the United States by comparing an employee’s Social Security number and other information against millions of government records.” Read the rest here and see the graphic.