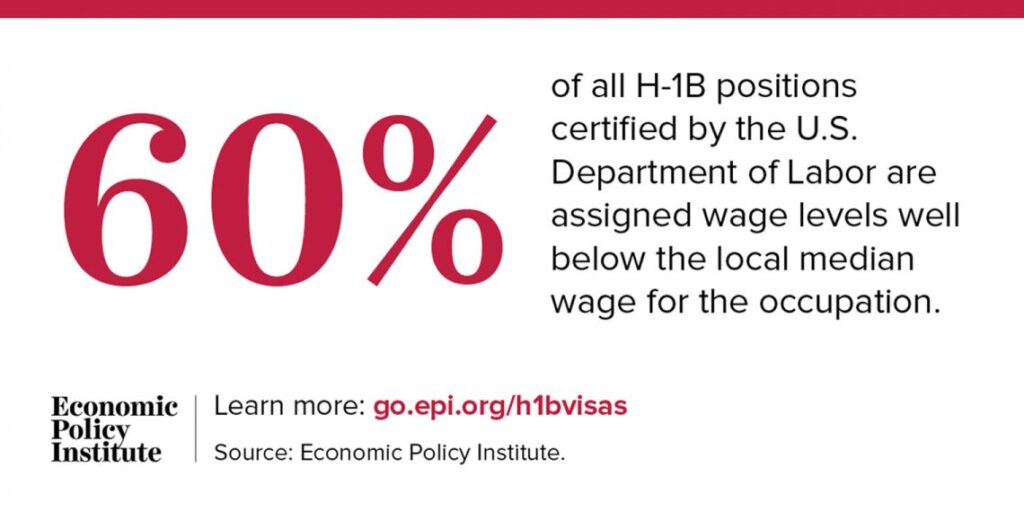

But what they really want is a steady supply of cheap, dependent IT workers.

Weeks before she lost her job, Judy Konopka’s desk was already clear. Gone were the photos and plants, the vintage typewriter and illustrated calendar. The wall where she had once tacked up a print-out of an inspirational quote was bare. By the time she walked into the brisk New England winter air on her last day, exiting the building where she had worked for the better part of two decades, Konopka didn’t have so much as a box to load into her 2007 Pontiac Vibe.

Konopka’s departure from Northeast Utilities in 2014 wasn’t billed as a layoff. Her employer’s merger with a Massachusetts power company would eliminate 350 jobs “through attrition,” the chief executive officer said when the deal closed in 2012. For a while, the staff believed it. The tie-up created a $12 billion company that eventually became Eversource Energy, with about 4 million customers across New England. Management gave reassurances that there would be more than enough work to go around after the deal, Konopka recalls — there was even a flutter of anticipation about the chance to do projects on Cape Cod.

But group by group, over the course of several months, teams were being displaced. Konopka, a web designer, was one of about 200 information technology employees to be laid off. Several not only had to watch their jobs go to foreigners, but also to train their replacements.

Many new hires were H-1B visa holders — mostly young, educated guest workers hired for “specialty occupations” such as engineering or computer programming that require at least a bachelor’s degree. Created in 1990 as part of President George H.W. Bush’s plan to expand legal immigration, the program had an initial cap of 65,000 approvals each year.