United States Citizenship and Immigration Services

Public Charge Provisions of Immigration Law: A Brief Historical Background

Historical Origins of the Likely to Become a Public Charge (LPC) Exclusion

Strong sentiments opposing the immigration of “paupers” developed in the United States well before the advent of federal immigration controls. During the colonial period, several colonies enacted protective measures to prohibit the immigration of individuals who might become public charges.[1] In the nineteenth century, before the existence of a federal agency responsible for overseeing immigration policies, eastern seaboard states such as New York and Massachusetts enacted state laws that restricted the immigration of aliens deemed likely to become dependent on public institutions such as poor houses. These states also charged steamship companies a “head tax” for each foreign passenger they landed in order to defray the cost of caring for, and sometimes removing, indigent immigrants who ended-up in state-funded facilities.[2]

Steamship companies, merchants, and others who favored open immigration challenged state head-taxes as impediments to free commerce. In response, state charity boards argued for the necessity of the head-tax in funding the care of foreign-born paupers and favored stronger protective laws to prevent additional influxes of destitute immigrants who could not support themselves.[3] The legal dispute over the state head-taxes reached a turning-point in 1875, when a lawsuit challenging the practice brought by a shipping company against the Mayor of New York reached the Supreme Court.[4] The Court decided that the state-imposed head-taxes interfered with Congress’s authority to regulate commerce and struck them down. Fearing the loss of funds needed to administer immigration policies and care for poor immigrants, eastern states began to lobby Congress for a federal immigration head-tax to replace the defunct state taxes.

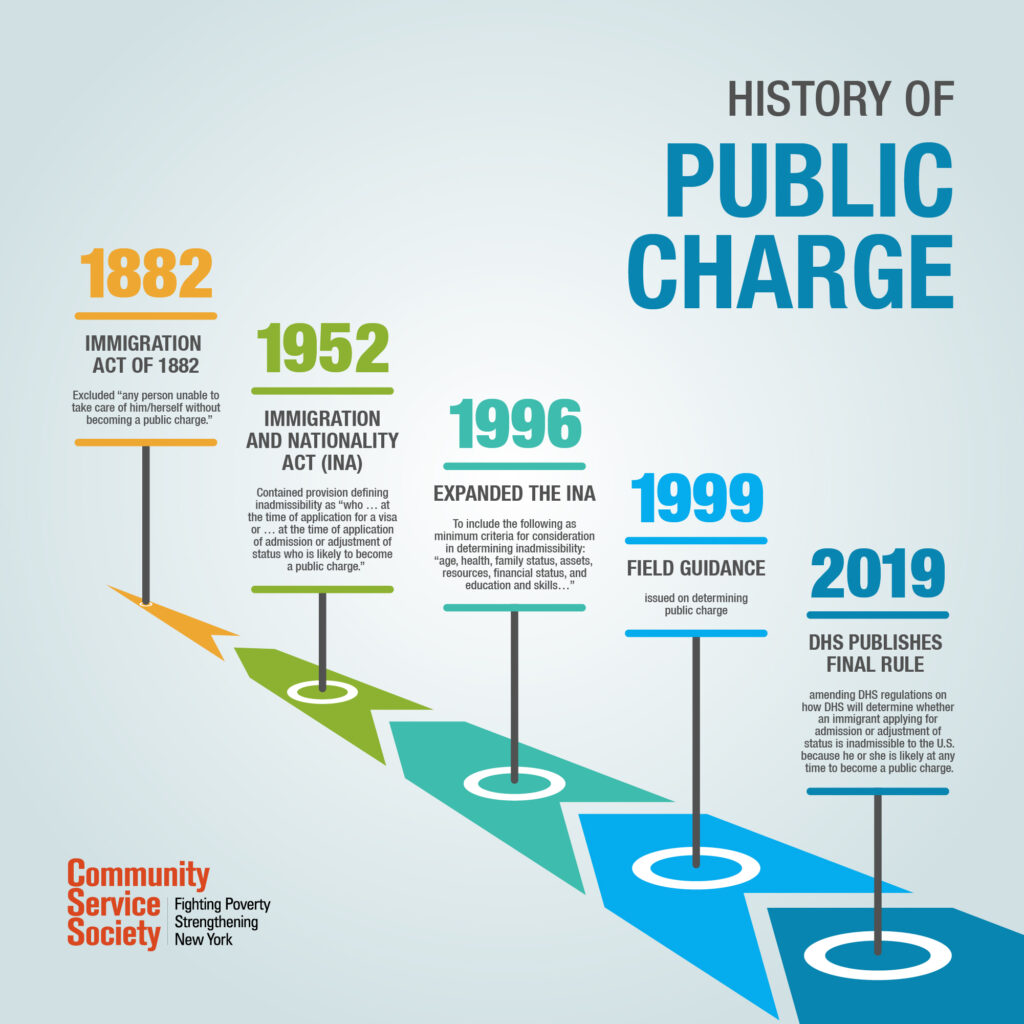

The eastern states’ concerns about poor immigrants and the cost of caring for them found expression in the first general federal immigration statute of 1882.[5] The 1882 law excluded “any person unable to take care of himself or herself without becoming a public charge.”[6] The 1882 Immigration Act also created a federal immigration head-tax, which was used to defray the cost of regulating immigration and to care for immigrants who arrived in the U.S., including those who fell into economic distress. However, the law did not create a federal immigration agency; instead it authorized the Secretary of the Treasury to enter into contracts with state immigration commissions to administer federal policies. Thus, in many ways, the 1882 federal law depended on state immigration commissions, who enforced the public charge exclusion policy and used money from the federal immigration head-tax fund to pay state and local charities that cared for immigrants.

While the 1882 federal law did not provide any definition of a “public charge” or any guidelines for determining who was likely to become one, state Immigration Commission reports suggest that officials took numerous factors into account, including an immigrant’s willingness to work, when making decisions in LPC cases. For example, in 1884 the Pennsylvania Board of Commissioners of Public Charities reported that a large number of Hungarians who were “poor, pecuniarily” were permitted to land because they were “strong, hearty people, and quite willing to work…”[7] In other cases the state boards landed questionable immigrants upon receiving guarantees from charitable organizations and/or bonds from the steamship companies that would be paid if the immigrants became public charges.

The general Immigration Act of 1891 completed the federalization of immigration regulation by creating the office of the Superintendent of Immigration and a federal Immigration Service to inspect all arriving aliens.[8] The 1891 law also retained the head-tax provision and the exclusion of “paupers or persons likely to become a public charge.”[9] In the Act of March 3, 1903 Congress added “professional beggars” as a class of exclusion.[10] A 1907 law then added additional language that excluded potential immigrants with a “mental or physical defect being of a nature which may affect the ability of such an alien to earn a living.”[11] The Immigration Act of 1917 added “vagrants” to the LPC provision and this version of it remained substantially unchanged when it was incorporated into the 1952 Immigration and Nationality Act.[12] The INA left the LPC policy substantively the same, but added language explicitly emphasizing the discretionary authority of administrative officers in the Department of State and the Immigration Service to determine the definition of “LPC.”[13] In sum, a version of the LPC provision has been part of federal immigration policy from its foundations and it consistently remained one of the most common grounds for immigrant inadmissibility.[14]

Brief History of Laws Providing for the Removal of Aliens Who Have Become Public Charges

In addition to providing for the exclusion of likely public charges, U.S. immigration law has long provided for the removal of immigrants who become dependent on public aid. The Immigration Act of 1891 established the federal government’s authority to remove aliens who entered unlawfully, a category that included immigrants who could be shown to have entered when they were LPC.[15] The 1891 Act also provided a deportability period of one year after arrival for immigrants who actually became public charges as the result of a condition that existed prior to their arrival. Congress extended this deportability period to two years in 1903 and three years in 1907[16]. The immigration Act of 1917 altered this provision, stipulating that aliens who became public charges “from causes not affirmatively shown to have arisen subsequent to landing” within five years of arrival were subject to deportation.[17] Additionally, the 1917 law removed the time limit on deportation: if an immigrant was shown to have become a public charge within five years of arrival they could be deported at any time, no matter how long they had resided in the U.S. The 1952 INA retained the provision that aliens who became public charges within five years of their arrival due to causes not affirmatively shown to have arisen since their entry could be deported at any time, and this has remained in the law since.

The Immigration Act of 1917 also provided for the removal at public expense of aliens who “fall into distress or need public aid from causes arising subsequent to their entry and are desirous of being so removed.”[18] Though not formal deportation, this law provided a means for the federal government to remove indigent aliens who desired to return to their home countries. During the Great Depression many aliens departed the United States under this voluntary provision.

There is much more here.